This past month with Viking has been pretty interesting. After getting through the basic syntax of Ruby we went even deeper into object orientation.

###Mastermind OOP wrapped up with recreating the classic board game Mastermind. The main point of the exercise was to drive home the ideas behind method decomposition, classes, and other basic principles of OOP.

However I had the most fun getting Mastermind to break my codes using Donald Knuth’s algorithm. Properly optimized the software can break a code in five guesses.

The idea is that the software first makes a list of every possible code (in regular Mastermind that’s 1296 codes). It then makes a pretty standard first guess. Like red red green green.

The real magic of the method didn’t make sense to me for a while. The software gets feedback on its first guess, like say one spot is exactly correct (black peg) and one is the correct color but in the wrong position (white peg). The software runs through the list of all 1296 possible codes, eliminating any that wouldn’t at least get that feedback. Then it makes another guess and another elimination pass. And so on, until it cracks the code.

def get_guess(last_feedback=nil)

if last_feedback == nil

@last_guess = [:r, :r, :g, :g]

else

@code = @last_guess

@possibles.keep_if do |p|

feedback(p).count(:black) >=

last_feedback.count(:black) &&

feedback(p).count(:white) >=

last_feedback.count(:white)

end

sleep 1

@guesses -= 1

@last_guess = optimal_guess

end

end

def optimal_guess

@possibles.sort do |px,py|

(feedback(px).count(:black) + feedback(px).count(:white)) <=>

(feedback(py).count(:black) + feedback(py).count(:white))

end

@possibles.pop

endThe above is my code for this. And here is the software cracking a code I set.

I’ve had to focus on writing code that actually makes sense to someone besides me when I’m writing it. Just a few weeks later and those two methods read like the Voynich Manuscript.

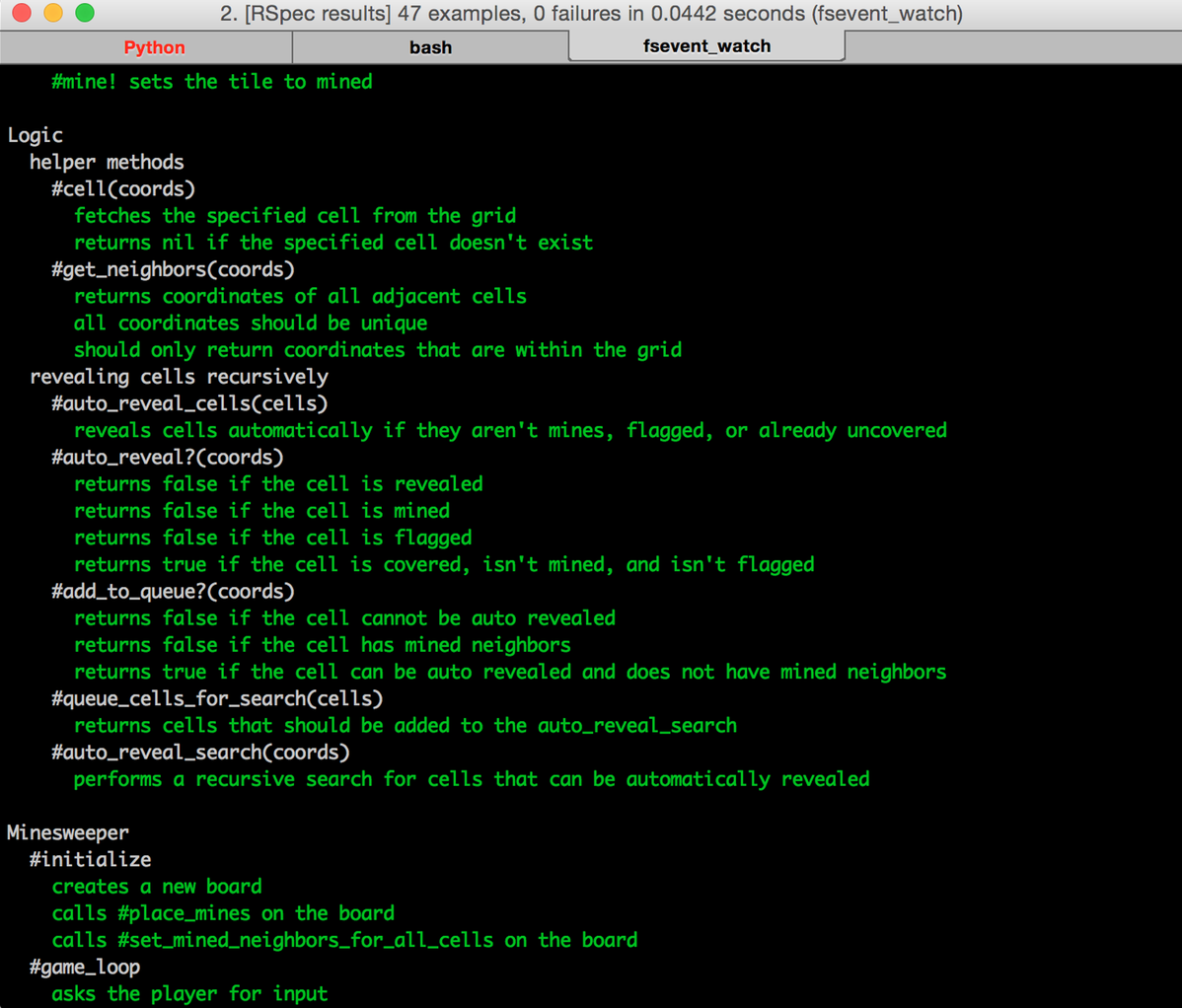

###TDD Minesweeper

The next unit focused on test driven development with Rspec. I had a little experience with this from Michael Hartl’s Rails Tutorial. TDD and Rspec are definitely frustrating to get started with. You’re constantly thinking about what to test, if you’re being too granular, if it wouldn’t be best to just run a higher level integration test that should fail if a dependent method breaks.

Despite the frustration, it is a great feeling to revisit well tested code, to refactor it confidentially as you watch your tests re-run with each change.

Minesweeper also presented an interesting problem to solve. A recursive function is needed to automatically clear cells when it makes sense to do so. It should clear the cells or tiles of the board right up to any tile that is adjacent to a mine.

This required a lot of different dependent functions. You’d need something that could find the “neighbors” of a cell. You need to add those neighbors to a queue and then come back and check all of their neighbors and so on until there was nothing left to check.

def get_neighbors(coords)

row = coords[0]

col = coords[1]

neighbors = []

possible_neighbors = [

[row-1, col-1], [row-1, col], [row-1, col+1],

[row, col-1], [row, col+1],

[row+1, col-1], [row+1, col], [row+1, col+1]]

possible_neighbors.each do |neighbor|

unless cell(neighbor) == nil

neighbors << neighbor

end

end

neighbors

end

def auto_reveal_search(coords)

queue = [coords]

until queue.empty?

test_cell = queue.shift

neighbors = get_neighbors( test_cell )

queue += queue_cells_for_search(neighbors)

auto_reveal_cells(neighbors)

end

endI’m a lot happier with this code than I was with Mastermind, initially the auto_reveal_search was one huge method that I was able to break down into a half dozen smaller ones. TDD definitely forces a lot of this discipline. If its hard to test, its probably bad code.

I’m now in the midst of data structures and estimating the time complexity of software using Big O notation. To infinity… and beyond.

(Sorry, that’s sort of the perfect way to end something when you’re talking about Big O)